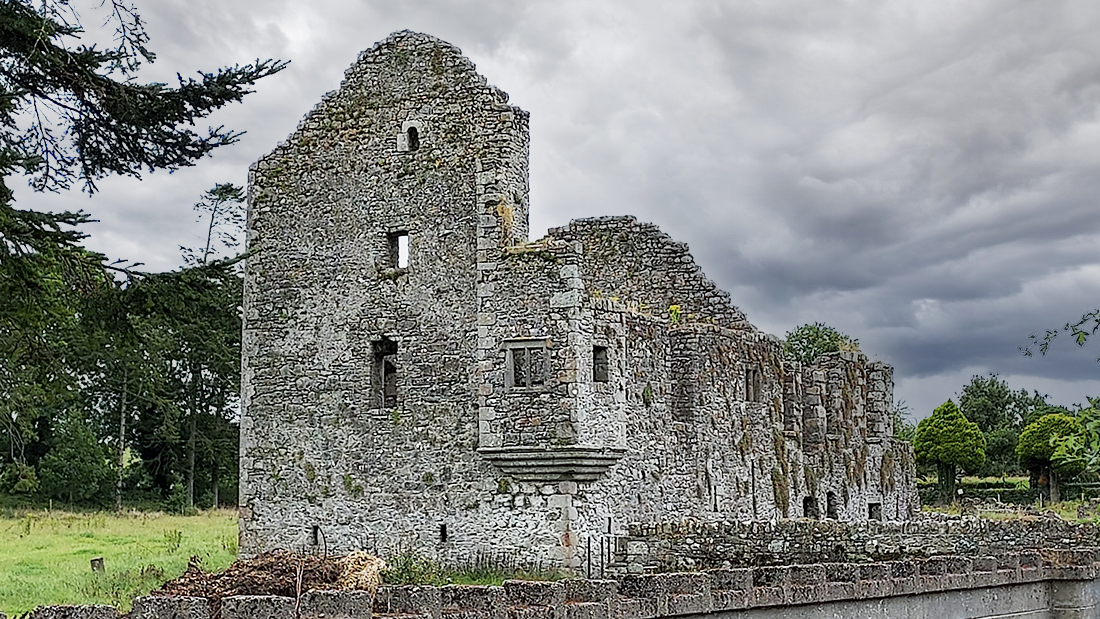

Muff Castle

Muff castle was built in the 15th century by Conor O’Reilly of East Breifne. Castle-building seemed to run in the family as Conor’s father, Conor Mór, built the castle at Cloghballybeg in Mullagh. The O’Reillys held Muff Castle until the end of the 16th century when they lost possession to the Flemings, who happened to own another castle nearby at Cabra, Kingscourt. During the rebellion of 1641 the Flemings sided with the Confederate rebels, leading to the capture and destruction of Muff Castle by Oliver Cromwell.1 The remains of the castle were later torn down to build labourer’s cottages.2 The Fair of Muff has been held on the site of where the castle once stood since at least 1608,3 although it probably dates back much further, possibly to Celtic times and the Festival of Lughnasa.

Robertstown Castle

This 16th century castle was owned by the Barnwall (Barnwell, Barnewell) family and was probably built by Alexander Barnwall, whose grave slab is at Robertstown church dated 1596.4 The Barnwalls arrived in Meath from Dublin in 1349,5 however a manor is recorded as already existing here in 13116 which was burnt following a Gaelic Irish attack. The manor in this case would have centred on the nearby motte which predates the castle. The castle is officially classed as a ‘Fortified House’, which was a type of castle built in the late 16th century that replaced the typical Tower House design found throughout Ireland. Fortified Houses, like the one in Robertstown, were protected by turrets projecting from the walls and gunloops. It is recorded that in 1640 the castle was in possession of an “Irish papist” called Margaret Barnwell, who had on her land “a castle, a church out of repair, a mill, a fishing weare and some cabins”.7

Ardamaghbreague Castle

The castle at Ardamagh was traditionaly known as ‘Castlecam‘ (the Crooked Castle) and was in possession of the Plunketts at the time of the Civil Survey. Following the 1641 Rebellion, the Plunketts were dispossessed of their lands by Thomas Taylor, a Surveyor, who came to Ireland to assist with the Down Survey and later acquired Headfort Demesne in Kells. Taylor leased the Ardamagh estate back to the Plunketts but they were evicted yet again following the Battle of the Boyne, and despite a lengthily court case never regained the property.8 Castlecam is recorded as being in ruins in 1836 and there are currently no visible remains. Of the descendants of the Ardamagh Plunketts was Eleanor Plunkett, who was the love interest of the blind harper Turlough O’Carolan from Nobber.

Newcastle

During the 17th century most of Moynalty parish was owned by the extended Betagh family. By 1640 Henry Betagh owned all the land around Newcastle, including the castle, which was already in ruins by this date. It is not known who originally constructed the castle. During the Nine Years War Henry appears to have helped the Elizabethans, as a letter survives from him to Sir George Carey giving details on the movements of the O’Neills.9 However, he seems to have switched sides during the Cromwellian War and was subsequently dispossessed of Newcastle and about half of his estates. It would appear that Henry was a shrewd operator though as according to the Down Survey he did manage to gain possession of a few new townlands. Of the castle, only the remains of a bawn wall survive which is now part of a farm building.10

Walterstown Castle

According to the Civil Survey John Betagh owned the land at Walterstown along with “an old ruinate castle and a few cabins”.11 As with Newcastle, it is not known who originally constructed Walterstown Castle or how long they resided there before the Betaghs came into possession. The extended Betagh family owned almost all of Moynalty parish in the 17th century only to lose it following the Cromwellian War. John Betagh was dispossessed of all his land and Walterstown passed to Hugh Culme, who also gained Moynalty townland, Rathmanoo and vast estates in Cavan. The foundations of the castle survive in Garryard Wood on the summit of a hill, though nothing is left of the main structure. The name ‘Garryard’ is taken from the Gaeilc ‘Cathair Ard’,12 meaning ‘High Seat’. This could refer to the castles prominent location on the hill, or could suggest that it was once the residence of a local ruling lord or king.

Crochawella

Crochawella, as it is known locally, translates from Gaeilc as the ‘Hill of Homes’ and was the site of a Norman castle, roadway and medieval buildings. The site can be found in the townland of Donore, which itself translates as the ‘Proud Fort’, and hints at an existing pre-Norman stronghold. The old village of Moynalty was located between Crochawella, the Church of Ireland and Deignan’s Field13 (a few hundred yards out the Carlanstown road); and dates to at least 1302. We know this as a church is listed in the ecclesiastical taxation of Pope Nicholas IV (1302-06). At the time of the Civil Survey, William Betagh owned “a castle, 3 stone houses with bawnes and cabins”14 at Crochawella, though only a mound now remains. The Down Survey mentions that there was another castle nearby, on the opposite side of the river, however this may have been referring to the motte,15 which still exists there, and not an actual stone castle. It would seem likely then that when the Normans first arrived in Moynalty they built the motte before establishing a more permanent settlement at Crochawella.

Flemings’ Castle, Cabra

Gerald Fleming built a castle at Cabra in 160716 on what was land formerly owned by the O’Reillys, although a much earlier castle built by Hugh de Lacy may have already existed here.17 When Gerald died his estate passed to his son Thomas, and then to Christopher Fleming, Baron of Slane, around 1624.18 In 1641, the Gaelic Irish and Hiberno-Normans united and rebelled against English rule in Ireland. This resulted in the Cromwellian War, and the Flemings – having sided with the rebels, were ultimately stripped of their castles at Cabra and Muff. The Flemings were later pardoned and regranted much of their lands but lost them again after the Williamite War (1688-91). Christopher Fleming, like many other Hiberno-Norman lords, sided with James 2nd and was outlawed for high treason in 1690. An 18th century house which was built over the site of the castle can still be seen in Dun na Rí forest park.

Cloghballybeg Castle

The castle at Cloghballybeg was built by Conor Mór O’Reilly in 1485, possibly over an earlier structure.19 It was located on a promontory that juts out into Mullagh Lake though no trace of the castle now remains. In 1610, Sir William Taaffe came into possession of 1000 acres around Mullagh following the Ulster Plantation and is said to have repaired and resided in the castle for a period.20 In 1614, Taaffe sold the manor to Edward Dowdall of Rathmore, who was a major landholder in Meath.21 A descendant of Edwards, Lawrence Dowdall, was in possession of the castle at the time of the 1641 rebellion, after which it was reportedly destroyed by Cromwell. Following the rebellion, Dowdall was confiscated of his estates in Mullagh in 1668.22

Corlat Castle

The ‘Manor of Kilcronehan’ was a 400 acre estate granted to Sir John Elliott on the Cavan/Meath border near Mullagh. The castle here was attributed to him “to hold forever, as of the castle of Dublin, in common socage, and subject to the conditions of the Plantation of Ulster”.23 In Pynnar’s Survey the manor is also called ‘Muckon’ and it is mentioned that “there is a Bawne of lyme and stone 60 feet square, and a small, house, all the land being inhabited by the Irish“.24 The ‘land being inhabited by the Irish’ would insinuate that the locals remained as tenants after being dispossessed. The castle appears on the 1835 O.S maps on a slope leading down to the river, although there were no remains at the time of Davies’ survey in 1948. At the time of the 1641 rebellion the castle was in the hands of Lawrence Dowdall.25

Breakey Castle

According to local tradition there was reportedly a castle situated at Breakey Lake on the hill beside the woods. There is no mention of the castle on the Civil or Down Surveys, but according to local folklore it was owned by the Plunketts of Ardamagh and subsequently destroyed by Cromwell,26 with the stones of the castle then being used to build the ‘big houses’ in the locality. The field in which the castle was located also appears in the Meath Field Names Project as ‘Castle Hill’.27

Eden Castle

The Civil Survey states that Kilmainhamwood “hath theron a castle a church and a mill all wast.”28 At this time the entire parish was owned by Nicholas Barnwell, though he did not live locally and was based in Dublin. It is not known who built the castle in Kilmainhamwood or how long it had been in ruin when the survey was carried out. The castle may have been located in Eden as a tower is depicted here on the County of East Meath map of the Down Survey. An image of a tower, this time on a mound, also appears in Eden on the Kells Barony Map of the Down Survey. The mound may indicate that the castle was simply a Norman motte and not a building constructed of stone, and according to local tradition a motte (and later a monastery) stood on the hill opposite the entrance to the old graveyard.29 So whether there was a motte or stone castle in Kilmainhamwood is not known, but either way some sort of defensive structure was present in Eden, although in ruins, in the mid-17th century.

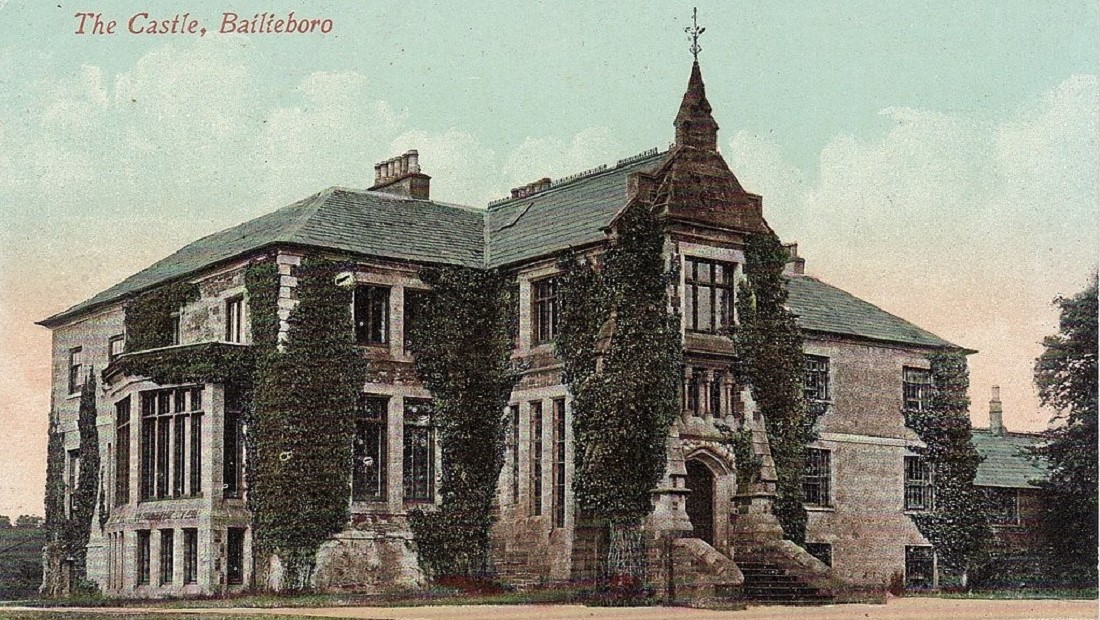

Bailieborough Castle

William Bailie, a Cromwellian planter, constructed a castle here in the early 17th century on or near the site of an earlier ‘ancient fortress’. Captain Pynnar, when conducting a survey here in 1619 on the status of the plantation, noted that there already existed here “a vaulted castle, with a bawn 90 feet square, and two flanking towers”.30 The castle seen its fair share of strife over the years and was occupied by rebel forces led by Hugh O’Reilly during the 1641 Rebellion. In the leadup to the 1798 Rebellion, too, rebels were trained on the castle grounds and trees in the castle demesne were cut down to make pike handles. In 1814 the castle was sold to William Young who developed and laid out the town of Bailieborough into its current location.31 William’s son, John Young, received a peerage in 1870 and became Lord Lisgar. From then on the castle was also referred to as ‘Lisgar House’. A religious order, the Marist Brothers, were the final long-term occupants of Lisgar House before it burned down in 1918. It was reoccupied briefly but demolished in years to come.

References

- Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, 2nd Edition, Vol. 2 (London, 1840), p. 408

- Featured in ‘Muff and its Fair’ in Breifny Antiquarian and Historical Society Journal, Vol. 1 No.1 (1920), p. 60

- ‘Fair of Muff 1608-2008’ information board erected at Muff crossroads, Aug 12, 2008, by Brendan Smith T.D, (Sep 4, 2022)

- National Monuments Service, Monument ME011-006, Available at https://maps.archaeology.ie/HistoricEnvironment/ (Feb. 14, 2022)

- Abraham Kennedy, ‘Upward Mobility in Later Medieval Meath’ in History Ireland Magazine, Features, Issue 4 (Winter 1997), Medieval History (pre-1500), Medieval Social Perspectives, Vol. 5

- B.J. Graham, ‘Anglo-Norman Settlement in County Meath’ in Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature Vol. 75 (1975), pp. 223-249

- Robert C. Simington (ed.), The Civil Survey, A.D. 1654-1656. Vol. 5: County of Meath, with the returns of tithes for the Meath baronies. Irish Manuscripts Commission, Dublin Stationary Office (1940), p. 357

- National Monuments Service, Monument ME005-055, Available at https://maps.archaeology.ie/HistoricEnvironment/ (Feb. 14, 2022)

- Valentine Farrell, Not So Much To One Side (Moynalty. 1984), p.105

- National Monuments Service, Monument ME004-007, Available at https://maps.archaeology.ie/HistoricEnvironment/ (Feb. 14, 2022)

- Simington (ed.), The Civil Survey, A.D. 1654-1656. Vol. 5, p. 300

- Valentine Farrell, Not So Much To One Side (Moynalty, 1984), p. 12

- Farrell, Not So Much To One Side, pp. 22-26

- Simington (ed.), The Civil Survey, A.D. 1654-1656. Vol. 5, p. 302

- Meath County Council, ‘Moynalty Architectural Conservation Area Statement of Character’, December 2009, p. 9

- O. Davies, ‘The Castles of Co. Cavan: Part II’ in Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Third Series, Vol. 11 (1948), p. 93

- Dún na Rí Forest Park official website, Available at http://www.dunari.ie (Jun. 20, 2022)

- Davies, The Castles of Co. Cavan: Part II, p. 94

- Philip O’Connell, ‘Historical notices of Mullagh’ in Breifny Antiquarian and Historical Society Journal, Vol. 1 No 2 (1921), pp. 117-120

- O’Connell, ‘Historical notices of Mullagh’, p. 127

- Davies, The Castles of Co. Cavan: Part II, p.105

- Philip O’Connell, ‘Parochial history of Killinkere’ in Breifny Antiquarian and Historical Society Journal, Vol. 3 No 2 (1929), p. 253

- George Hill, An Historical Account of the Plantation in Ulster at the Commencement of the 17th century 1608-1620 (Belfast, 1877), p. 343

- O’Connell, ‘Historical notices of Mullagh’, p. 128

- Davies, The Castles of Co. Cavan: Part II, p. 105

- The School’s Collection, Vol. 0706, ‘Hidden Gold’, p. 203, Available at https://www.duchas.ie (Feb. 16, 2022)

- Meath Field Names Project, Available at http://www.meathfieldnames.com (Aug. 24, 2020)

- Simington (ed.), The Civil Survey, A.D. 1654-1656. Vol. 5, p. 312

- Danny Cusack, Kilmainham of the Woody Hollow, Kilmainhamwood Parish Council (1998), p. 8

- Samuel Lewis, A topographical dictionary of Ireland, Vol. 1 (1837), p. 99

- Leslie McKeague, ‘Bailieborough – A Rich History’, Available at http://bailieborough.com/history/a-rich-history (Dec. 26, 2022)