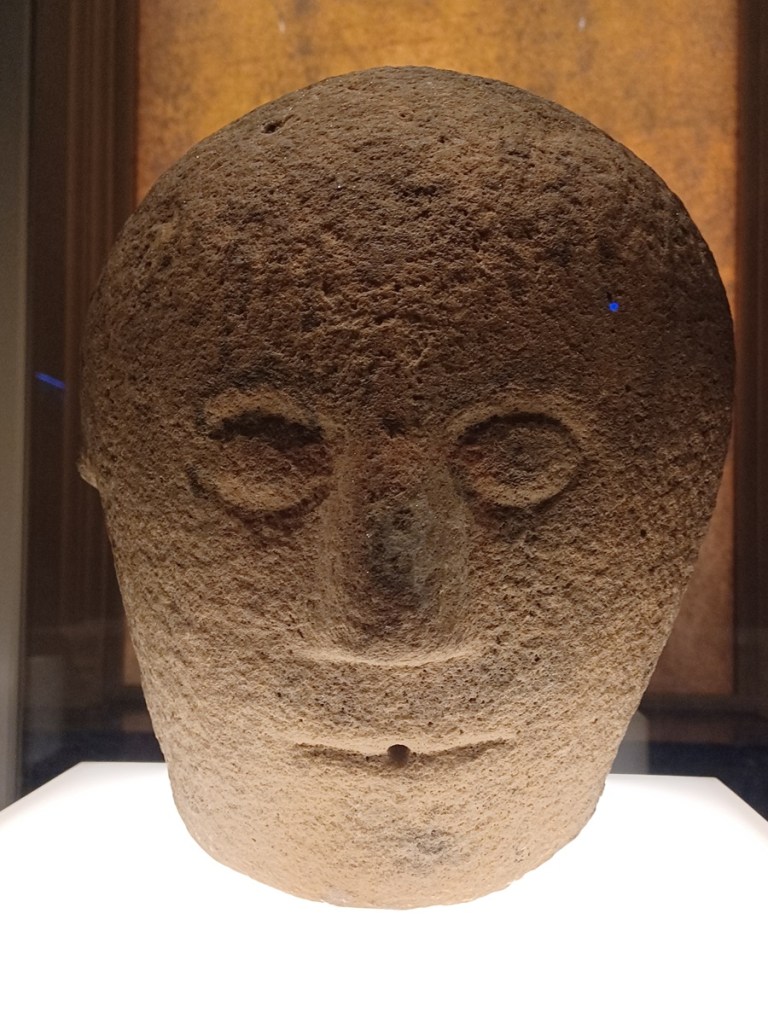

The Corleck Head is a three-faced stone idol found near Corleck Hill, Bailieborough in 1855. It is believed to date to the 1st or 2nd century AD, during the Iron Age, based on it’s similarity to other Celtic artefacts from northern Europe.

Corleck Hill has been a site of ritual activity since the Neolithic period, as seen by a now lost passage grave dating to around 2500 BC. In the late Iron Age, the hill became an important religious centre and was associated with the Lughnasadh harvest festival. One of the names for the hill in Irish is Sliabh na Trí nDée (Hill of the Three Gods).

Carved from a single block of limestone, the head features three similar faces with protruding eyes, thin mouths, and unsettling expressions. A hole at its base suggests it may have been mounted on a pedestal or shrine. The three-faced form may represent Crom Dubh, a Celtic harvest god who hoards the yearly grain. A younger god, Lugh, must defeat Crom Dubh to seize the grain for humankind.

The Corleck Head was likely buried between to protect it from Christians seeking to erase pagan symbols, especially those associated with human sacrifice.

Sources

Dáithí Ó hÓgáin, The Sacred Isle: Belief and Religion in Pre-Christian Ireland (Woodbridge, 1999), pp. 36-39

Michael J. O’Kelly & Claire O’Kelly, Early Ireland: An Introduction to Irish Prehistory (Cambridge 1989), pp. 290-94

Marion McGarry, Irish Customs and Rituals: How Our Ancestors Celebrated Life (Orphen Press, 2021), pp. 56-62

Seamus MacGabhann, ‘Landmarks of the people: Meath and Cavan places prominent in Lughnasa mythology and folklore’ in Ríocht na Midhe 11 (2000), pp. 219-38 (21 pages)

Morgan Daimler, Pagan Portals – Irish Paganism: Reconstructing Irish Polytheism (Hants, 2015), pp. 52-54

Bailieborough.com, ‘The Corleck Head,’ Available at http://bailieborough.com/corleck-head/ (May 21, 2025)

100objects.ie (by An Post, The Irish Times, the National Museum of Ireland, and the Royal Irish Academy), ‘Corleck Head,’ Available at https://100objects.ie/corleck-head/ (May 21, 2025)